Funding up, academic performance down in Michigan schools

Only 5% of Detroit 8th graders proficient in math

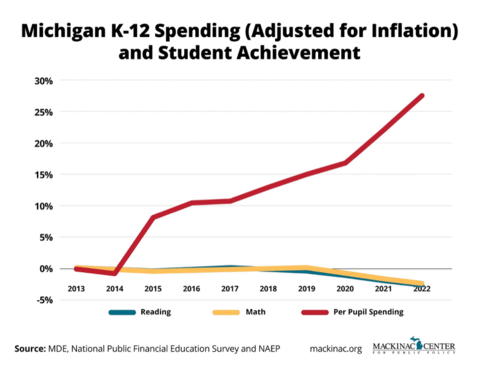

Michigan has spent heavily on early childhood education over the past 20 years, but it has not brought better academic outcomes. While spending increased, student proficiency dropped.

In fiscal year 2000-01, Michigan’s education spending on the School Aid Fund reached $10.8 billion. By fiscal year 2023-24, spending had more than doubled to $21 billion, according to the nonpartisan Senate Fiscal Agency.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer expanded taxpayer funding for preschool in the latest budget.

The move mirrored an earlier expansion of government involvement in early education by former Gov. Jennifer Granholm, who formed the Early Childhood Investment Corporation in 2005.

“It is critical that we provide opportunities to stimulate and feed children’s minds by providing every child the opportunity for high-quality education and care,” Granholm said at the time.

Fourth grade is typically when students start falling behind. In 2000, Michigan’s fourth grade students performed above the national average on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the nation’s report card.

Nationally, the average NAEP score for fourth grade math in 2000 was 224, and Michigan scored 229. Only 11 states scored higher. The national average for reading in 1998 — there was no test in 2000 — was 213. Michigan had a higher score, 216 and ranked 18th in proficiency.

On the latest assessment, in 2023, the average national score for math was 235. Michigan trailed, with an average of 232. It now ranks 36th in math.

The results are similar for reading. Michigan’s average of 212 trails the national average of 216. Now the state ranks 41st.

In Detroit, 90% of students in public elementary and middle school are either not proficient or only partially proficient in English, according to Molly Macek, education policy director at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Only 5% of eighth graders are proficient in math.

Michigan’s K-12 education system has struggled for 20 years, Christian Barnard, assistant director of education reform at the Reason Foundation, told Michigan Capitol Confidential.

“The state’s public schools have seen some of the largest enrollment declines in the country, and student achievement on national tests has stagnated or declined despite increases in per-student funding,” Bernard said. “State leaders should focus on improving core K-12 education, not funneling tens of millions in new dollars towards pre-K.”

Michael F. Rice, superintendent of public instruction for the Michigan Department of Education, did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Michigan is making progress, according to Bob Wheaton, a spokesman for the Michigan Department of Education.

“In the National Institute for Early Education Research Annual Yearbook, Michigan’s pre-kindergarten program continues to be tied for first in quality but is 18th in access, with a little more than one-third of all 4-year-olds enrolled in GSRP preschool last year,” Wheaton told CapCon in an email.

Since Granholm, the budget for early childhood education has gone up to at least $780.4 million for the 2024-25 school year. That includes $609.7 million in general funding, $42 million for early literacy coaches, and $25 million in start-up grants.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Michigan Education board member claims funding cuts after record funding

Michigan Education board member claims funding cuts after record funding

Whitmer admits education system failing despite increased spending

Whitmer admits education system failing despite increased spending

Educator behind embattled reading theory to keynote Troy School District conference

Educator behind embattled reading theory to keynote Troy School District conference

Michigan House resolves to disclose enhancement grants, recipients

Michigan House resolves to disclose enhancement grants, recipients

.jpg) Four Michigan orchestras get $2.34 million in 2025 budget

Four Michigan orchestras get $2.34 million in 2025 budget