What are the Real Motives Behind Asset Seizures?

Law enforcement veteran says its about the money while a lawmaker works to solve the problem

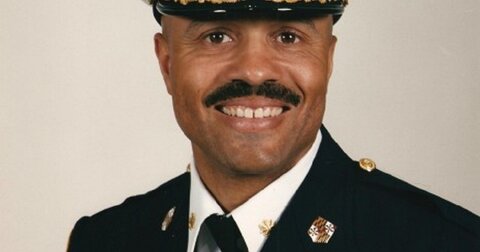

“I had a team of people and their only job was to find me money,” said retired Maryland State Police Narcotics Commander Maj. Neill Franklin.

Franklin is the executive director of LEAP, Law Enforcement Against Prohibition. He now travels the world speaking on behalf of legalizing marijuana.

It isn’t that the church-going, former undercover officer is a fan of the drug, but his 34 years in law enforcement have convinced him that the war on drugs has failed and is now mostly a money-making arm for police departments small and large.

“At the beginning, we really thought that we could keep drugs out of our communities but when I was assigned to the division of corrections investigative unit, I realized we couldn’t [even] keep drugs out of our most secure buildings in our state, which were our prisons,” Franklin said.

Franklin began reevaluating his views on the drug war after doing his own observations and research and losing his close friend in a drug sting.

Seeing the violence and losing a friend was enough for his about-face but it was not so obvious in the world in which he worked. He started to see why: bad incentives. The drug war gives law enforcement agencies access to federal funding and the opportunity to seize the property of suspected users.

Civil asset forfeitures began under President Ronald Reagan as a tool to cripple the operations of major drug dealers. Forfeitures are separate actions outside criminal warrants and allow police to seize property, freeze bank accounts, and take money suspected as profit from criminal activity.

But “suspected” is a loose term and Franklin began to see police broadening the asset forfeiture net, taking money and property from anybody who had any amount of drugs on them or in their cars.

“We had no indication of them selling or using,” he said. “These were people who were addicted to drugs and we used those civil asset forfeitures to take their belongings.”

He added: “We would use the seized money and property to finance our drug enforcement operations. If I didn’t have that money, it would have been very difficult for me to balance my budget. I may have had to lay some people off.”

He noted that the seizures made little or no impact on drug use, but they did create jobs for the department.

“Since we started this war on drugs, it is 60 to 70 percent of what we do in our communities,” Franklin said. "It’s become our identity and, unfortunately, the law enforcement community has a hard time imagining what we would do if the drug war ended today.”

The Maryland State Police says it does not comment on public remarks by retired officers.

Civil asset forfeitures do not involve only alleged drug crimes. Police can seize property for other suspected criminal activity – a list that gets bigger by the year. According to an analysis by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Michigan has created an average of 45 new crimes annually over the past six years, a significant percentage of which are administrative in nature and don’t require proof of criminal intent for police to seize assets.

At the federal level, Michigan’s Tim Walberg has introduced the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act. The bill, proposed by the representative from Tipton, requires a tougher burden of proof in seizing property, changing it from “preponderance” to “clear and convincing” evidence. It also shifts the “innocent owner defense” from the government to the property owner, making summary judgments for defendants easier. Right now, the onus is on the owners in federal forfeiture cases to prove they are innocent.

Federal reform can be instrumental to state reform because law enforcement in states can resort to looser federal forfeiture laws and split the value of property proceeds with federal agencies.

Walberg is working in conjunction with U.S. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, who has introduced his own legislation, the Fifth Amendment Integrity Reform Act. Both bills are expected to be reintroduced once the new Congress is sworn in.

“I’m certain there will be more than the 20 sponsors that I currently have that cross the political spectrum from libertarians to full-blown liberals," Walberg said. "I think there is a real interest now that information is coming up on people, like the Dehkos in Michigan.”

Terry Dehko and his daughter run a grocery store in Fraser, Michigan. The Internal Revenue Service emptied the small business’s bank accounts based on a pattern of cash deposits that agents believe were linked to criminal activity. The IRS backed down after the Institute for Justice filed suit and an investigation showed the store owners were innocent, but their money was frozen for almost a year.

As for seizing assets for suspected drug activity, Franklin says communities would be much better off if police redirected their focus.

“I’ll tell you what we’d do: We’d fight violent crime, murders, rapes, robberies, and domestic violence,” he said. “We can pay more attention to those and crimes against our children.”

~~~~~

See also:

Property seized, Money Taken - But No Crime

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

U.S. House bill raises the bar for federal civil asset forfeiture

U.S. House bill raises the bar for federal civil asset forfeiture

Whitmer creates second Michigan education department

Whitmer creates second Michigan education department

Federal court severely curtails civil asset forfeiture in Michigan

Federal court severely curtails civil asset forfeiture in Michigan