Michigan Motorcycle Deaths Decline Since Helmet Mandate Repeal

State police data shows fatalities and injuries down, despite media reports

A Grand Rapids doctor generated national headlines with his study that claimed motorcyclist head injuries and deaths have increased sharply since the state repealed a mandatory helmet law in 2012.

Dr. Carlos Rodriguez, the author of the study, said that he noticed a spike in injuries and deaths while working in the trauma unit at Spectrum Health Hospital.

"Injuries soar after Michigan stops requiring motorcycle helmets," is what the Reuters news service said in a headline.

But statistics compiled by the Michigan State Police don’t support a claim of a large increase in motorcycle-related injuries or deaths since the helmet law was lifted.

“We are reporting what we are finding (at Spectrum Health Hospital)," Rodriguez said. "That's the only thing we can report."

His study looked at 345 individuals treated at the West Michigan hospital for motorcycle crashes during the months of April through October during the years 2011 through 2014. The helmet law was repealed in April 2012.

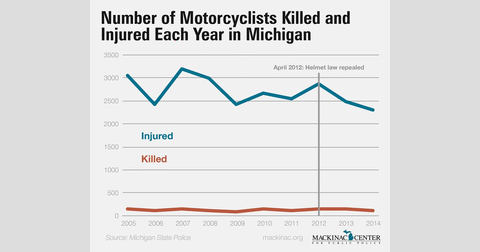

The state police data on motorcycle accident deaths and injuries don't show an increase in the first two years after the helmet law was lifted.

In 2012, 129 people were killed in Michigan motorcycle accidents and 2,870 injured. Those numbers dropped to 128 and 2,497 respectively in 2013. In 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, 107 people were killed and 2,309 injured.

Between 2005 to 2011, while the helmet mandate was still in effect, an average of 114.2 people were killed each year in Michigan motorcycle accidents and 2,757.6 injured. The state police data shows no clear trend.

Sierra Medrano, a spokeswoman for the Michigan State Police, said all traffic crashes are reported to the state police.

"By law, all law enforcement agencies are required to submit qualifying crash reports (reports made using the UD-10 State of Michigan Traffic Crash Report) to the MSP," Medrano said in an email. "The UD-10 Traffic Crash Report Instruction Manual provides law enforcement officers with instructions on what crashes [to report] and how to record them correctly."

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Trust Parents with Schools of Choice

Don't restrict opportunity for 'historically disadvantaged' student groups

It doesn’t take much to trigger one education official’s strong instinct to constrain parental choice, a reaction not justified by the evidence. State Board of Education President John Austin misused a study on Michigan’s Schools of Choice program to try and make the case for curtailing parents’ ability to find a school that best fit their children’s needs.

The Schools of Choice program is a policy first enacted in the late 1990s that allows Michigan families to enroll students in other traditional public schools across district lines. It is extremely popular with parents.

A recent Bridge Magazine story highlights this by looking at a first-of-its-kind 2015 study by Michigan State University professor Joshua Cowen and graduate student Benjamin Creed. Following a December 2013 Mackinac report that identified long-term growth in Schools of Choice participation, the MSU study found a continuing trend. Between 2002-03 and 2012-13, inter-district choice nearly tripled — from about 40,000 to 115,000 students — even as the state’s overall public school enrollment declined by 180,000.

Factoring out student characteristics that impact test scores, Cowen and Creed found that participation in Schools of Choice yielded, on average, no discernible achievement gains for students on state tests. This finding prompted a drastic overreaction by the State Board of Education President.

Austin was quoted in the Bridge article: “Unrestrained choice is an unmitigated disaster for Michigan. Cross-district choice is less about learning than about competing for students and money.”

To begin, the Schools of Choice program is hardly “unrestrained.” Under Section 105 of the School Aid Act, local districts have the option whether to participate at all, and can set various caps on out-of-district enrollment. Local districts establish application procedures, and determine whether to accept students only from neighboring districts or from neighboring intermediate school districts, which usually are farther away. The state prevents any participation beyond a neighboring ISD.

Austin would take that constraint even further. He reportedly told Bridge that Schools of Choice students should receive less funding. The MSU study found that “historically disadvantaged” student groups, African-Americans and those in poverty, are most likely to enroll across district lines. His proposal would create incentives that further restrict an opportunity disproportionately used by kids who have more challenges to overcome.

The MSU study found a neutral impact, but it did so based only on standardized test scores. These scores are one key measurement of the value a school adds to a child’s education, but not the only one. And Cowen makes this clear in a blog post about the study: “[Schools of Choice] does not appear to be hurting achievement, overall, so it’s reasonable to consider other ways of measuring its success.” Austin would have been wise to consider this fact before launching his tirade against parental choice.

Parents opt to use interdistrict choice for reasons other than just trying to increase standardize test scores, such as physical safety, academic offerings, extracurricular opportunities, school culture or special programs more aligned with their children’s aptitudes. This latest research suggesting Schools of Choice does no academic harm is not a sufficient cause for robbing parents of the ability to choose a school for these other legitimate reasons.

Austin’s view of Schools of Choice holds the interests of government agencies, in this case school districts, above those of parents and students. Since Schools of Choice isn’t “working,” this thinking goes, get rid of it so as to make life easier for school officials by making it easier for them to budget from year-to-year.

This differs significantly, of course, from a view that places the interests of parents above those of school districts. Parents know better than anyone else the needs of their children, and thus should have the right to choose the best school for their child.

Since Schools of Choice appears to do no harm while providing several unmeasurable benefits to parents and students, it should be continued and even potentially expanded. It’s unfortunate that Austin entirely neglects this point of view in denouncing a popular school choice program.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Follow us on social media!

Push back on big government “solutions” by becominga fan of us on Facebook and X. Plus you can share free-market news to your network!

Facebook

I already follow CapCon!

More From CapCon