Mackinac Center Survey Finds One-Third of Ga. School Districts Contract Out Services

Contracted custodial services are most popular

Authors’ note: The following was first posted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation August 27, 2015.The Mackinac Center’s annual survey of conventional public school district contracting was expanded this year to include four other states.

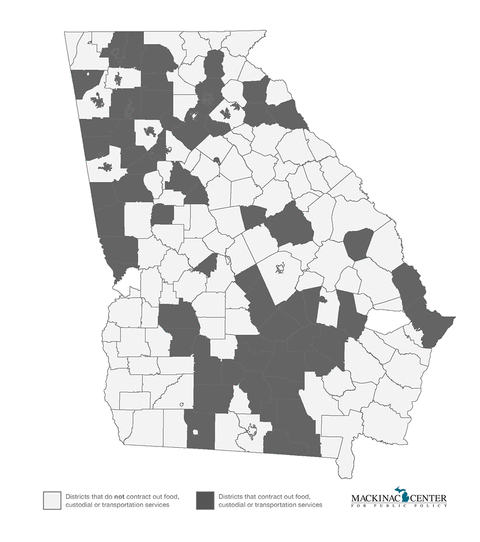

More than a third of all conventional public school districts in Georgia contract out one of the three major noninstructional services, according to survey data collected this summer by a the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan-based research institute.

The Mackinac Center survey of Georgia and four other states found that 38 percent of Georgia districts contract out for at least one of the “big three” noninstructional services: food, transportation and custodial services.

Done right, contracting out can save money and relieve management headaches, too. But Mackinac found a curious pattern in Georgia: Just three districts — 1.7 percent — contract out transportation (bus) services, and only four, or 2.2 percent, contract out for food services.

These are the lowest food and transportation outsourcing rates among the states surveyed: Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Texas.

While this finding might suggest hostility to competitive contracting, such a conclusion belies the fact that 36.7 percent of Georgia school districts use private vendors to provide custodial services.

So why do districts appear comfortable contracting in one area but not others?

When done correctly, privatization can both improve service and reduce costs by 10-20 percent or more. In research going back more than 10 years, the Mackinac Center has found that privatization saved Michigan school districts from $35 to as much as $191 per pupil, depending on various factors.

The Mackinac Center also found nothing inherently problematic about contracting for transportation or food services compared to custodians. Ten years ago, only 3.8 percent of Michigan school districts contracted out for transportation services; today, that figure stands at 26.6 percent, and 42.8 percent for food services (see graph). In Pennsylvania, 66.5 percent of districts contract out some or all of their bus services, and 44.4 percent do so for food.

The Mackinac Center sought answers for the divergence in two places. First, it asked school district officials in their survey interviews. They provided no particular reason to explain why so many districts outsourced janitors but not the other services.

It also investigated whether some provision of state law may be responsible. The research, while not exhaustive, revealed no obvious obstacles.

All this suggests that competitive contracting for food and bus services could be ripe for expansion in Georgia schools. Few district superintendents would turn down an extra $100 per pupil in savings, which is essentially what happens when districts forego this opportunity.

If competitive contracting was not a useful management tool, far fewer schools in states like Michigan and Pennsylvania would embrace it. By their actions, school superintendents there have demonstrated that the practice that can save money and improve quality.

As Georgia continues to investigate education funding, this timely survey by the Mackinac Center highlights an opportunity ripe for school systems to create savings and shift more funding into Georgia classrooms.

Michael LaFaive is director of the Morey Fiscal Policy Initiative for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Michigan and Kelly McCutchen is president and CEO of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Michigan bill to unravel privatization of non-instructional services heads to Whitmer’s desk

Michigan bill to unravel privatization of non-instructional services heads to Whitmer’s desk

Conservation officers may soon need warrants to enter private land

Conservation officers may soon need warrants to enter private land

Michigan gives $250,000 to a private school

Michigan gives $250,000 to a private school

Schoolchildren, Teachers, Taxpayers Harmed When Pension Managers Assume Too Much

The realities of Michigan's $26.5 billion pension liability

State law requires the managers of Michigan’s school employee retirement system to base annual pension contributions on an assumption that its investments will generate an average return of around 8 percent per year. If the actual returns don’t reliably meet or beat that level over time, it means contributions into the pension fund will be insufficient to pay for the retirement benefits of employees. The result is a long term unfunded liability that taxpayers eventually have to pay.

Michigan’s school pension system has put taxpayers on the hook for a $26.5 billion unfunded liability. The 6.5 percent return earned by its investments over the 12 months that ended June 30 means the hole got a little deeper last year.

Several state pension officials quoted in a recent MIRS News article about the shortfall noted that missing investment targets for one year is not a big deal.

They’re right, but what they didn’t mention is that this is not just a one-year problem. A 2014 auditor general report examined and found problems in some of the key assumptions used to estimate how much is needed each year to adequately fund the pension system. Failing to reach assumed investment return rates was the largest contributor to pension underfunding over the 10-year period examined.

This is hardly a surprise. Even before the 2008 recession, funding assumptions were not working to fully fund pensions. In fact, in 2003 Warren Buffett suggested that 6 percent is more realistic, and others routinely recommend 5 percent.

At their current $26.5 billion level, Michigan’s unfunded school pension liabilities are 13-times the total amount of state government debt owed to every general obligation bond holder. It’s equivalent to 88 percent of all the money the state will spend this year on schools, prisons, welfare and everything else (not including federal dollars). It would require an additional payment of $6,900 from every household in Michigan to satisfy this liability.

However, don’t expect state and school political leaders to say much about failing to meet the system’s Pollyanna funding assumptions, which were placed in statute by their predecessors in previous legislatures. Realistic assumptions would expose the entire system as an increasingly unsustainable house of cards. More to the point, current legislators would then have to find more money to cover the much higher annual contributions that better assumptions would make necessary.

The system is still a mess even with overly optimistic assumptions helping to mask the gaps. The state has only saved enough to cover 60 percent of every dollar’s worth of pension benefit that employees have earned. The underfunding has caused annual contribution rates to swell to 33.41 percent of school payroll, with 86 percent of this needed just to catch up on the past underfunding — underfunding enabled by the unrealistic assumptions.

In other words, taxpayers today are devoting more than a billion dollars each year to pay for previously earned pension benefits — money that would otherwise be available for other important needs.

To put that 33.41 percent figure in text, private-sector retirement benefits tend to cost 5 to 7 percent of payroll.

Going forward, the problem and solution are clear: Governments cannot be trusted to run a defined-benefit pension system, and Michigan’s should be wound down as quickly as possible.

For starters, that means closing the system to new employees, who would instead receive employer contributions to individual retirement savings accounts. This would contain the underfunding problem.

Unfortunately, whenever this is proposed pension managers are the first to object. In addition to downplaying missed assumptions, they bring up illusory “transition costs” as a barrier to converting.

Missing funding assumptions is a big deal and state officials should not shrug off this failure. Pension underfunding hurts taxpayers and threatens the retirement of hundreds of thousands of people. It harms schoolchildren by draining other classroom resources. The underfunding problem cannot be quickly or easily solved but the damage can be contained by not enrolling new employees in the current plan.

Michigan Capitol Confidential is the news source produced by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Michigan Capitol Confidential reports with a free-market news perspective.

Follow us on social media!

Push back on big government “solutions” by becominga fan of us on Facebook and X. Plus you can share free-market news to your network!

Facebook

I already follow CapCon!

More From CapCon